These characters make bad decisions—it was important that the reader see how they got to that point

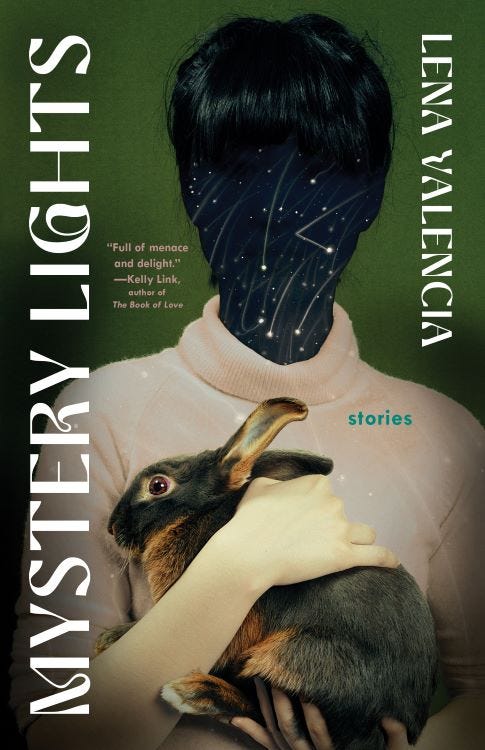

Book Talk with Lena Valencia: Mystery Lights, horror film, collaging

I’ve been in a short story funk for a while. Lena Valencia’s debut collection, Mystery Lights (Tin House, 2024), plucked me out of that. Mystery Lights is a sharp, gorgeous, and unsettling collection, rippling with flares of the fantastic. The ten stories of this book follow sisters, mothers, daughters, artists, and influencers in the desert, looking for UFOs, and violently seeking to define their lives on their own terms.

In “The Reclamation,” a women’s “entrepreneurial wellness and self-actualization boot camp” led by a Goopy lifestyle guru goes wrong. In “Trogloxene,” a girl’s sister goes missing in a cave during a family trip and returns with dark visions of cave dwellers who are clawing her back to them. “Bright Lights, Big Deal,” follows a young woman who’s moved to New York and wants to make a name for herself in the art world, telling her story of self-interest and deceit in hypnotic second person.

Lena is a Brooklyn-based writer. She’s the managing editor and director of educational programming at One Story and is co-host of the Ditmas Lit reading series. We spoke about the collection, grifts, conspiracy theories, and horror movies.

We're about a month past the release now—how are you feeling? How is it hearing what people are saying about the book?

It's been really wonderful, in all honesty. In the lead up to pub date I was very, very anxious. There were all good things happening—a lot of this anxiety was, as most anxiety does, coming from within—but I feel like after the launch and the first couple of events, I was mostly just getting wonderful responses from readers and from friends and family who'd read the book, which was amazing.

Along the way, meeting and reading with other writers, I'm in a really good place now. It's been really incredible. These stories were so private for so long. I showed them to my writing group, and I had a handful published in literary magazines, but otherwise not many people had read them before they were published in the collection. It's been wonderful hearing kind words from readers, some of whom are strangers.

I can imagine having the book come out is like emerging from the cave, and then suddenly it's out in the world.

You can't put it back in there. It's out of the cave.

I'm always interested in the way writers develop collections of stories or essays, and I wonder when you started to see Mystery Lights coming together as a book. When did it feel like this was a cohesive project?

Yeah, it was pretty early on in the process. I'd written the title story, and I was applying for a grant. I had one collection that I had pretty much finished and started sending out to agents, but it didn't really have a coherent thread running through it, or it did, but it wasn't quite working. I’d just written “Mystery Lights,” the title story, and I had the idea of having stories connected by place because place has always been really important to my fiction.

While writing that story I was thinking about the desert and how people interact with the desert wilderness. I decided to try to write more desert stories. Then all of my connections to the desert came out. My grandparents are from Tucson, and I spent a lot of time out there as a kid. Being from Southern California originally, a lot of trips were to the Mojave, spending time in Joshua Tree. As I was writing and researching the collection, I traveled to more deserts in the Southwest.

What elements of people's relationship to the desert were you interested in, and why does that feel like such a rich place to explore? As you started to write, what became more curious or unusual to you?

I think I was specifically interested in setting supernatural stories in the desert. I find the landscape to be kind of unreliable in its own way. I remember driving through Big Bend National Park in West Texas, and it was so hot outside—so you're already a little woozy—and then seeing these cliffs in the distance and not realizing how big they were. That kind of uncanniness, that disconnect—I held onto that, and I wanted to use that in in these stories that dealt with the supernatural.

I also think any wilderness, but the desert in particular, is a place where if you go unprepared, you will interact with place whether you like it or not. I wanted to use that. A lot of these women are going into this place and are not familiar with it. They're not really thinking about the responsible way to be in the landscape and in nature. I wanted to explore that conflict in the stories.

It's such a great backdrop for horror and the uncanny. In the collection, there are ghost stories, conspiracy theories, and grifts. These stories that people hear can exert pressure on them. How were those themes generative for you?

That's a good question. I think, specifically for “The Reclamation,” I was interested in exploring how someone can be grifted and converted, and I chose wellness culture. It was in the middle of lockdown, and I was listening to a lot of podcasts about cults, and also self-help podcasts. I started fusing the language from those two. It was important to me to use a character who was initially skeptical of the charismatic leader, and to watch her gradually change her mind.

With the two ghost stories, the ghosts are somewhat beside the point. With “Reaper Ranch,” I wanted to explore a widow’s grief. With “Clean Hunters,” I was thinking about the effect a well-intentioned lie can have on a relationship.

Cults and self-help can create narratives to organize someone’s life. I was really struck by how you explored, on a smaller level, the power of a person's story for their own life. “Trogloxene” and “The Reclamation” both feature these gripping passages where the narrators feel dark thoughts about inflicting pain on others. I was impressed by the bold narration and how you build towards a fever pitch. That becomes a new organizing logic or something for the character to resist. How did you uncover those dark gems?

I think that we all have dark thoughts from time to time, and I was just imagining what would happen if these characters acted on these impulses. I'm really glad that you found that thread between those two stories. In “Trogloxene,” Holly, takes a certain amount of pleasure in not having her sister Max around when Max goes missing. But she feels guilty for this, and it’s clear by the end of the story that she gets no joy from the outcome. “The Reclamation” takes a different tack—rather than reckoning with her guilt about a violent act she committed as a child, Pat finds a way to twist it around into a dark power.

I think that we all have dark thoughts from time to time, and I was just imagining what would happen if these characters acted on these impulses.

Another story that I think carried that thread through was “Bright Lights, Big Deal,” when Julia decides to share a traumatic event from her friend’s life for clout on her blog, telling herself that she’s “a crusader for justice.” These characters make bad decisions, but it was important to me that the reader see how they got to that point.

In contemporary fiction, there can be a discourse about writing that’s risky. I was impressed by the place you accessed with those characters, and the trust you had with the reader to understand.

“Bright Lights, Big Deal” is written in second person, and the narration felt rhythmic and propulsive. The voice and point of view are working in tandem, and it felt intoxicating to be brought into it. What did it feel like to write that story?

Thank you for saying that. Writing in the second person doesn't leave the same room for exposition, slowing down, and gentle, beautiful description that writing in the third person or the close third does. It’s similar to first person in that way, and I thought that that kind of clip was appropriate for that character and what she was going through—the confusion and the wildness of being in New York City as a young person. I also thought it mirrored her; she has this kind of youthful narcissism, and I could imagine her telling this story about herself in the second person.

I loved the vision she has of what her life should be as an artist. There’s an entitlement on one hand and a pretty harsh critic on the other.

You included research notes at the end of your collection. What books and media were inspirational for you?

One big inspiration for me as I was starting to write the book was Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey, and his relationship with the land. I think a lot of the characters in this book he would not approve of, but I was almost writing against it in a certain way, writing people that would not feel the same way he did about the land.

Another writer whose work has always been a guide for me is Shirley Jackson. The way she writes these social dynamics, whether or not she's using the supernatural, I think she's really great at that. Kelly Link is another writer who's always been really inspirational to me. I was reading her work while I was working on some of the stories in this collection, and I hope that it came through a little bit.

I do love horror movies. I wanted to transport the reader in the same way that you feel transported when you're watching a horror film. There’s this one indie horror film called The Wind that tells the story of two women who live with their husbands on a remote plot of the prairie in 19th-century New Mexico. There are elements of the supernatural that come into play, but what the film does best is use the sound of the wind to ramp up the horror and the isolation of their situations. Some of these independent horror movies make use of very little, and they use that to scare, which I admire.

It sounds like a sort of atmospheric pressure, which is what I really felt in this book.

Yeah.

I want to ask about your other creative work. You work in visual art, and you're the managing editor of One Story. How do those practices complement or interact with your work as a writer?

At One Story, I’m on the educational side of the organization, in addition to managing the production of the magazine. I read the short story that's coming out every month because I'm putting it into layout, and I think that's been really educational. I think if any writer reads a short story a month, they will learn a lot. Many of my coworkers are writers who are further along in their careers than I am; I’ve learned a lot about how to maintain my own writing practice from them.

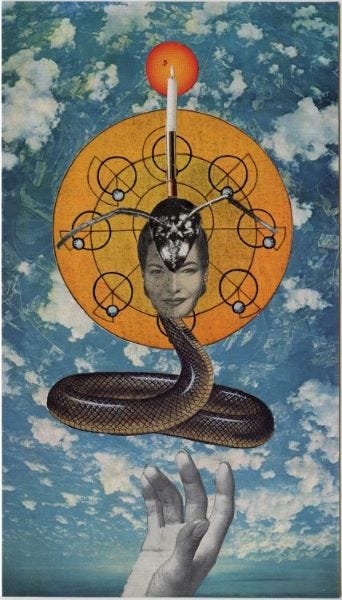

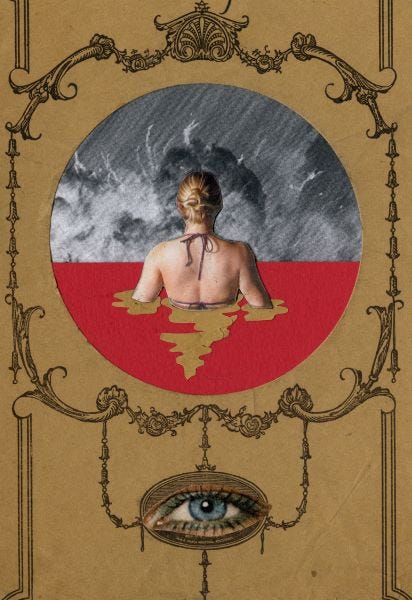

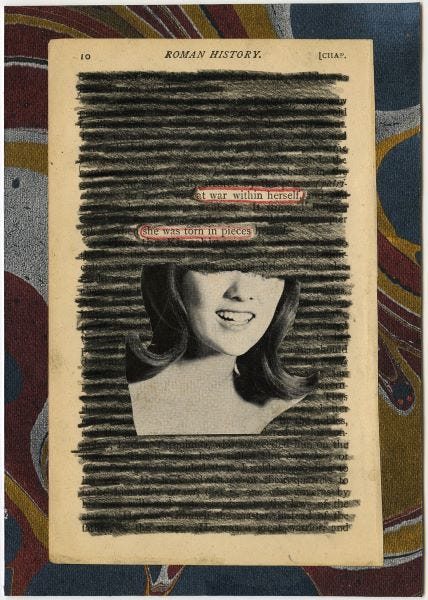

Collage was something I'd done in high school, and I did find that the way I was approaching it was similar to the way I was drafting. There are these overlaps: these ideas of juxtaposition, the surreal, and the uncanny.

In terms of collage, I was having some writer's block at the beginning of COVID lockdown, and I needed to do something where I wasn't staring at a screen because it was making me nuts. Collage was something I'd done in high school, and I did find that the way I was approaching it was similar to the way I was drafting. There are these overlaps: these ideas of juxtaposition, the surreal, and the uncanny. I find it to be a way to exercise a different part of my brain. I don't know why this is, but I find it a lot easier to sink into a collage than I do into a piece of writing. Maybe it's because I'm newer at it and I have fewer expectations, but it's been a really great side practice to have.

What else is exciting to you in fiction right now, whether things that you're trying in your writing or things that you're reading that are really inspiring? Are there new challenges that you want to take on?

I just read The Woman Upstairs by Claire Messud, and I cannot get the voice out of my head. I’ve been thinking a lot about that first person narrative and the way she writes about women's anger.

I've also been working on a horror novel—contemporary horror that's inspired by Dracula and the way that was put together—using the epistolary form and weaving together diary entries, emails, letters, and other documents to tell a story. That’s been really fun.

That sounds so cool. You mentioned voice, and I have to ask—the voice in these stories felt so strong and crisp. Does that feel like that’s one of the tools you're giving most attention to in your writing? Does it come naturally to you or is it something you've had to build and develop?

I can have a situation, a place, and some character traits sketched out, but it isn’t until I land on a voice that I can really start to build out a story. I hear other writers talk about being possessed by their characters, and that's something I can relate to. When I get a voice in my head, I have to write it down. I think in terms of developing it, one tool I use in revision is reading my work out loud to myself and listening to how a paragraph sounds, or how a conversation sounds. But mostly, when I’m drafting, I try to get out of my own way and let the voice lead me where the draft needs to go.

Order Mystery Lights here; if you’re local to Portland, hear Lena read from her collection at Print on October 7.

Reference Section

If you’re a Dracula fan and aren’t aware, you can sign up with Dracula Daily to get each installment of the novel emailed into your inbox. It starts every year on May 3.

In the spirit of influencers and wellness, I’m a longtime listener of the podcast Too Niche. They recently covered dopamine menus, which was entirely new to me. This episode provides a helpful introduction.

In Maine literary news, the MWPA Lit Fest began last Thursday. Check out the schedule—there are virtual events if you’re not local to Maine.

Late to the party, but I just finished the audiobook for Bad Blood (I think Theranos is low-key Little Shop of Horrors coded). I was so pulled into it—my mom overheard me listening once and said it sounded like a soap opera. I don’t particularly recommend the audio for it, but I definitely think the book itself is a fascinating read.

Note: I earn a small commission when you shop for books through my Bookshop links, and I appreciate your support, which helps keep Referential free.