Drag, mystic nun with daddy issues, how to read poetry (finally!)

5 Poetry Things with Joshua Garcia

“It wasn’t until I forgot and then remembered, / until their shapes turned like a room through the bottom of a glass / that I started to question the way I remember things— / the words I still feel hard against the back of my neck.”

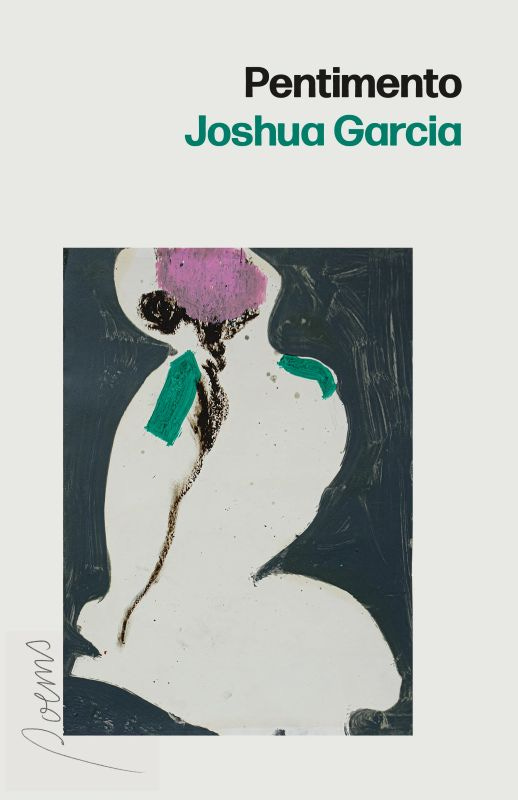

With crystalline focus, Joshua Garcia’s debut poetry collection, Pentimento, explores the intersections of body, health, sexuality, and faith. Bold, bodily, introspective, and sexy, the book weaves photos of the author through its examination of chronic pain and the speaker’s relationship to a faith that no longer fits him. The collection is one of my favorite books of the year so far and was recently named a finalist for the 2025 Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry.

When he went for his MFA at the College of Charleston, Joshua was a devout Christian and wanted to work on a manuscript about God and queerness.

“I knew that I wanted to write a book that dealt with those two themes, but I went in expecting for it to be an apologetics of queer faith,” Joshua said when we caught up over Zoom. “Through the process of writing the poems, my relationship to my faith completely changed, and it ended up being more about a renunciation.”

“When you're writing a poem about something, you're looking at it in a different way. I was paying attention in a way that brought up a lot of questions and truths that I hadn't realized yet,” he added “I was really asking lots of questions. I was paying attention to the experiences I was having. I was excavating what was happening to me, both spiritually and physically with chronic pain, which I think is tied into a lot of that experience, and socially within the church.”

We caught up on ekphrastic poetry, drag, revision, and faith.

5 Poetry Things

1. How to read poetry

One of the first things I talk about when discussing poetry with folks who are new to poetry is how to read poetry. Not that there’s any one way—that’s the opposite of the point I’d like to make—but if your subscribers are like me, they might feel like they don’t know how to approach poetry if it’s not already a part of their reading or writing lives. For many years, I didn’t read or write poetry because I didn’t know where to begin, and I felt like I didn’t know how to read it. This changed when a friend told me to read it like you read any other book: read a page, then turn the page. Simple! I could do that. Rather than flipping through a book of poems at random and trying to understand what any particular poem meant, I merely had to read a page, then turn the page.

Now I might read a poem twice before turning the page, especially if I’m enjoying the book, but I no longer feel the need to labor over each page until I understand the poem. Understanding is subjective. Paraphrasing Mary Ruefle, if a poem makes you feel something, if you’ve taken pleasure in it, you have understood it. I also encourage new poetry readers to engage with poetry as they would less narrative art forms like music or visual art. Listening to “Clair de Lune” or standing in front of a Rothko, we tend not to ask ourselves what it means but rather how does it make us feel? I invoke Rothko because people tend to have mixed reactions to his paintings. Some weep. Some shrug their shoulders and move on. Poetry is kind of the same—you don’t have to like everything you read. But if one painting doesn’t make you feel anything, that doesn’t mean you don’t like all art. Keep reading poetry. Keep listening to yourself as you read it. Ask yourself first, How does this make me feel? Then, if you want to dig deeper, ask yourself, Why?

2. Ekphrasis

I have a hard time talking about poetry without talking about art. Partly because poetry and art do similar work asking the big questions—why are we here? what is this experience of living?—and also because I like to write about art. And that’s what ekphrasis is: writing, usually poetry, about visual art. The word ekphrasis comes from the Greek ek (“out”) and phrazein (“to speak”), and early examples, like Homer’s description of Achilles’s shield in The Iliad, tended to speak imagined artworks into existence. Through time this evolved to writing about existing works of art and, in much contemporary ekphrasis, writing beyond the artwork itself—and that’s where I really fall in love with reading and writing ekphrasis.

I didn’t read or write poetry because I didn’t know where to begin, and I felt like I didn’t know how to read it. This changed when a friend told me to read it like you read any other book: read a page, then turn the page. Simple! I could do that.

In the way walking into a cathedral can quiet a person, standing before an artwork can be a contemplative, spiritual experience. Good art directs our attention outward and inward at once, and we carry that experience with us beyond the doors of a cathedral or a museum. Jim Whiteside’s poem “Objective and Relative Beauty” comes to mind. In the poem, the speaker encounters Gustave Caillebotte’s painting Floor Scrapers. The poem moves from the painting (“the men, the ringlets of old varnish”) to an erotic encounter in a museum bathroom and back to the painting. By the end of the poem, the speaker feels altered in an undefinable way, like “The other building, / barely visible beyond the balcony’s iron railing.” At its best, art casts the shadow of a becoming self before us, and what better way to explore that intangible experience than through poetry?

Objective and Relative Beauty

By Jim Whiteside

— Les Raboteurs de Parquet; Gustave Caillebotte; Oil on Canvas; 1875

The men are working harder than I ever will,

each holding a different tool for specific parts

of the job. I have loved them since I was young:

the men, the ringlets of old varnish. But here,

in the gallery, the familiar presents as new.

When the handsome stranger approaches, asking

to take me to the restroom and smell my armpits,

how can I deny him a pleasure I can provide

so easily? In the stall, he works quickly,

removing my shirt, breathing me in deeply.

Eyes closed, concentrating, locking in the memory.

When he is done, he looks me in the eyes,

gripping himself, breathing hard. I push the hair

from his forehead with my thumb. In principle,

I do not believe the theory that a painting’s singularity

is destroyed the moment you take its picture,

that meaning is lost in reproduction. But I will

admit: there is only one way for certain intimacies

to be known. Gold wainscotting. How it shines

as you cross before the canvas. The other building,

barely visible beyond the balcony’s iron railing.(Originally published in Poet Lore, Volume 119, Summer/Fall 2024)

3. Is poetry drag?

I often think of ekphrasis as a kind of drag, especially if taking on any personae found in an artwork, and this is leading me to wonder: is all poetry a kind of drag? If you’ve ever been in a writing workshop, you know that we refer to the voice in the poem as “The Speaker” rather than assuming the voice is the author’s. Sometimes a poet takes on a persona of someone else or even a persona of themselves. I’ve found myself explaining this to those close to me since my collection, Pentimento, was released last year and as some of my newer poems are published. Even though the poems in Pentimento, particularly, are very much me, they’re also only a part of me. Sometimes a distilled version of that part of me. Drag often exaggerates gender through performance and persona, reflecting truths about ourselves and our culture back to us. I find myself more and more leaning into this practice as I write—my own voice blurring with other people, characters, feelings, ideas, references—in search of a truth beyond the facts of my experience.

4. The Annunciation

If I did have a drag persona, in the Drag Race sense, she would definitely be modeled after the Virgin Mary or Margery Kempe or a mystic nun with daddy issues. Pentimento is in large part about my experience with faith and queerness (spoiler alert: it’s complicated). I don’t subscribe to any particular faith now, but I still believe in the “mystery.” Poetry and art satisfies some of the impulse that religion used to, and because it’s the language I was given, I still sometimes use the language of religion to talk about writing poetry or making art. For example, “the act of writing poetry is like prayer” or, as I’m about to explain, inspiration is like the Annunciation.

Pentimento is in large part about my experience with faith and queerness (spoiler alert: it’s complicated). I don’t subscribe to any particular faith now, but I still believe in the “mystery.”

In Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art, Madeleine L’Engle writes that “to paint a picture or to write a story or to compose a song is an incarnational activity.” For L’Engle, the creative impulse mirrors that of the biblical Annunciation in which it is announced to Mary that she will bear a child through miraculous conception. A mystical apparition, saying, in L’Engle’s words, “Here I am. Enflesh me.” Questions of consent abound in analysis of this narrative, but L’Engle argues that Mary could have said no and that, if she had, she would have gone on to live a good life, though a less miraculous one. This idea, as it relates to art making, has haunted me since I read Walking on Water maybe a decade ago. Inspiration is a part of my writing process, but only a small part. It’s mostly work. Hours of sometimes fruitless labor. But since reading L’Engle, when inspiration does come, I try to prioritize it above anything else. I could say, “No, later,” but I’m so afraid of what I might miss out on.

5. Revision

For any writer, revision might be the hardest part of the process, but it’s often where the good stuff happens. The title of my book, Pentimento, comes from an Italian word that means to repent. The word is used primarily when talking about instances in painting where an artist’s previous compositions, whether a draft or a completed work, can be seen through the final layers of paint. It’s visual evidence of revision on a canvas. I discovered the word while researching a painting by da Vinci, and it sat in my nameless manuscript for over a year before I realized the poems themselves were evidence of a revision in my life. A kind of pentimenti. You’ll find that revision is a common topic in writers circles or workshops. It’s essential and ever-challenging. How do you know when revision is still needed? How do you know when a poem is complete? Maybe you never do; maybe it never is. But the attention we give to this part of the process usually makes the work stronger. If there’s anything I’ve learned from poetry about life, it’s this.

Lightning Round

Favorite poet?

I feel like that's always a really hard question, because who I gravitate toward changes depending on what I'm writing or what phase of life I'm in. If I had to pick, either Frank O'Hara or Carl Phillips are the two that I return to the most.

Favorite poem?

I'm torn, but I think I'm going to say “The Layers” by Stanley Kunitz.

Favorite album?

I've been listening to Julius Eastman a lot, and he has this album called The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc. His work is just starting to get its credit. This album is instrumental with one completely a cappella track—I love it. I've been writing about Joan of Arc lately, and so I've been returning to that album.

Favorite spot in Brooklyn?

Prospect Park.

Best writing advice you’ve received?

Just to keep writing. A mentor in my MFA said a lot of people go to Iowa or to these other prestigious programs, and then they just completely stop writing after they graduate. The people that succeed, whatever that looks like or means to you, are the people that keep writing. It really made an impression on me that actually a lot of it is up to me, to keep doing the work and putting that effort in and hopefully that will pay off, or some people will recognize that at some point. It's just about the labor of writing and returning to your desk.

Order Pentimento, follow Joshua on Instagram and read more of his work here.

Reference Section

Sample some of Joshua’s poetry here in Split Lip (featuring a read on gay men having no sense of direction)

Who says books coverage is dead? For Organic Spa Magazine, I wrote about biophilic home design and managed to work in a mention of The City is a Rising Tide—how a couple camps on the land they’ve purchased to figure out how they want to live in their future home.

Last night, I read from my essay on my first gay crush, The Talented Mr. Ripley, and abjection at Noir in the Bar here in Portland. You can catch the full essay here on Hazlitt.